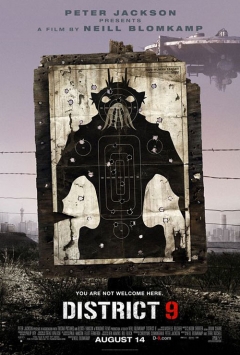

Directed by Neill Blomkamp (Key Creatives, 2009)

Two very different sci-fi films opened and closed Hollywood's Summer blockbuster season this year. The new Star Trek (Paramount Pictures, 2009) got things off with a bang in May, and District 9 (Key Creatives, 2009) is winding things down with a bit of a whimper this August.

The latest Star Trek rebooted Hollywood's oldest and biggest sci-fi franchise with an action-packed epic pitting a brand new version of the indomitable James Tiberius Kirk and his intrepid crew against yet another planet-destroying Romulan villain out to colonize the universe.

As in the previous five TV series and 10 motion pictures of Gene Roddenberry's long-running space opera, this Saturday afternoon swashbuckler paints a romantic utopian vision of a universe shaped by interracial, international, and intergalactic harmony. Indeed, since 1966 the crews and captains of Star Trek's various spaceships and space stations have looked and behaved like the ideal UN peacekeeping delegation, a rainbow coalition of smart collaborative folks working to bring civilization and harmony to the darkest edges of the universe. In this sci-fi franchise humans are friendly do-gooders who just want to get along and help out.

District 9 offers a decidedly bleaker and profoundly more self-critical vision of the future, reminiscent of the dystopias served up in sci-fi classics such as Blade Runner or the Alien, Terminator, and Matrix series. In District 9 humans do not work and play well – especially with "others."

Indeed, in this reworking of the classic alien invasion story, it is not the insect-like space travelers who imprison, abuse, and slaughter their new acquaintances. Instead, South African director Neill Blonkamp's film about intergalactic xenophobia tells an all too familiar tale of man's inhumanity to other creatures. It is the earthlings who are monsters.

Because so many sci-fi stories deal with our encounters with aliens, they invite us to reflect on what it means to be human, what counts as human. Like the lawyer in Luke's gospel, they ask who our neighbors are and what it means to be a neighbor-even an intergalactic one. And they occasionally raise uncomfortable questions about our own so-called humanity, suggesting that the aliens we fear and despise may be more "human" than we are.

In Ridley Scott's dystopian sci-fi classic Blade Runner, Harrison Ford must detect and destroy a rogue band of replicants who have returned to the home planet to wreak havoc on their creators. But our hero soon discovers that these "creatures" have as much humanity as the earthlings who created and posted them to hostile planets to wage our wars and work our mines.

Indeed, in Blade Runner, Alien, and The Terminator, we soon discover that the villainous replicants, machines, and aliens we wish to annihilate are human creations. Human engineers have built Blade Runner's replicants as android slaves. Politicians want to capture the Alien slaughtering Sigourney Weaver and friends to use as a biological weapon. And Arnold Schwarzenegger's Terminator is a third-generation machine originally designed by humans.

These are all Frankenstein stories in which the despicable beast has been made by human hands. These aliens are our creatures. Their monstrousness is our creation.

What is even more curious about these sci-fi films is how often the monsters and aliens in question are corporate productions. In Blade Runner, Alien, and Terminator, it is corporations that have built the replicants, hunted down the alien creatures, and designed the machines threatening to destroy humanity.

Likewise in District 9 it is a multinational corporation abusing and slaughtering aliens in our name. On the surface of these films, it seems like the alien creatures are inhuman monsters threatening to murder our women and children. But just below the surface lurks a more inhuman and soulless beast stripped of compassion or morality and obsessed with profit.

Frankenstein sci-fi stories have warned of the dangers of progress and technology, telling tales of monsters created by science run amok. But a number of sci-fi stories suggest that the inhuman monsters and creatures wreaking havoc in these tales are products of another modern creation-the corporation-and warn that in fashioning a soulless political and economic machine that pays no attention to morals we have unleashed the worst monster possible.

There were hardly any corporations when Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein, but in the last two centuries national and international corporations have mushroomed into giants bigger and more powerful than most nations. Though built and run by humans, they often operate with few or no concerns about the humanity of the people and communities they affect. They act as if they had no conscience and deny all responsibility.

It makes sense, then, that several dystopian sci-fi films would identify corporations as the inhuman machines behind the murderous creatures in these films. For although the corporate figures in these movies look much more human and civilized than the replicants, aliens, monsters and machines tearing up the countryside, they are often equally soulless and inhuman-perhaps even more so. Indeed, in these cinematic meditations on what it means to be human, the greedy, unfeeling corporation usually comes across as significantly less humane than the grotesque or murderous beast being hunted by our hero.

What, then, in these dark sci-fi films constitutes humanity? What makes us (or any other creature) human?

First, it is our ability to see the humanity of the "other." Just as Adam becomes human when he recognizes the stranger Eve as his own flesh and blood, and the Good Samaritan proves his humanity by responding to the humanity of the wounded stranger, so the humane characters in these sci-fi tales see the dignity and sanctity of the alien.

Second, it is our ability to acknowledge our own inhumanity, to know that much of the evil we see in the "other" has been projected there by us. As the human protagonist learns in District 9, our own inhumanity is as grotesque as anything we claim to see in the "other." And recognizing that is what makes and keeps us human.

Add comment