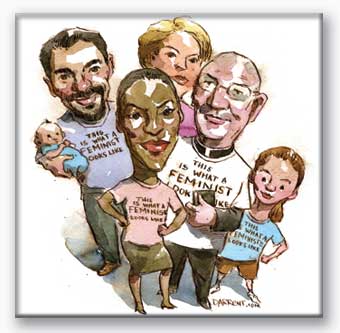

Catholics ought to be loud and proud in the fight for women’s rights, argues a young feminist.

I wasn’t burning my training bras or hating men (they weren’t yet on my radar screen, anyway), but my feminism was ardently liberal and a huge reason I struggled with my faith.

Over the past few years, I have become more immersed in the Catholic world, and I’ve learned that I’m not the only one who struggles with faith and feminism. There are, of course, many who reject Catholicism outright because of the lack of women in top leadership, and a few who courageously fight to change the 2,000-year-old patriarchal institution.

On the other hand, it seems that many vocal Catholics are saying, “I’m not a feminist.” For whatever reason—it’s too radical, man-hating, or pro-choice—a number of Catholic men and women deny or qualify feminism. By doing so, though, they are only hurting themselves and their sisters.

It’s time more Catholics, both men and women, opened up the conversation between these two points of view. I will always hope the church will treat women in its ranks more equally, but in opening this conversation, I also have come to see a positive relationship between Catholicism and an active feminism that aims to protect the rights of the most vulnerable. Because women, and consequently their children, still suffer the effects of poverty and other injustices more than men do, Catholics must fight for them.

Realizing this has allowed me to be as proud of being a Catholic as I am of being a feminist. For other Catholics, I hope reflecting on faith and feminism moves them to declare themselves proud to be feminists as well.

Apopular Catholic alternative to feminism these days is “new feminism,” Pope John Paul II’s idea that women should embrace their “feminine genius,” or capacity for physical and spiritual motherhood. New feminists defend the dignity of women who choose to stay home, a personal decision I admire, though I would not agree that all women are blessed with feminine genius simply based on gender.

My mother stayed home for nearly 20 years raising my brother and me, but she taught me that feminism extended beyond home life. Feminism is activism—protecting the rights of women in both the public and private sphere. As a feminist I raise women’s issues with friends and at work; I lobby for legislation and vote (knowing women have had this right for less than 90 years and currently hold only 16 percent of congressional seats); and I give to organizations that support women in the United States and abroad.

My greatest qualm with “new feminism” is that I think it is more about a personal decision than activism. Moreover it is not concerned with the “least of these” among us but instead with families that can afford to live off one income while one parent stays home.

An authentically Catholic feminism is not only about vocation or glass ceilings. It is about simply keeping the floor under women, respecting their dignity and rights as people.

Third World feminists challenge Western and predominantly white feminists to struggle not only with issues of gender but also those of race, culture, and class. This is essentially what Catholic feminism does. Catholic teachings on solidarity demand that we listen to the marginalized and oppressed. In this sense Catholic social teaching and feminism go hand-in-hand on many issues.

Catholics, for instance, take a feminist stance on workers’ rights. Issues like fair pay, family leave, and flexible scheduling allow women more equitable treatment at work, but they also promote the good of the family. This isn’t just about the do-it-all mom in upper management; it’s about families struggling to maintain a middle-class lifestyle with two salaries and single moms earning the minimum wage.

We need to fight for the likes of Lilly M. Ledbetter, who sued Goodyear when she learned she was paid less than the lowest-paid man at her level. Women, who still earn 78 cents for every $1 earned by men, were handed a setback when the Supreme Court ruled last May that complaints must be filed within 180 days of the first discriminatory pay decision, even if the employee only learns of the discrimination much later.

The ruling also violated Catholic principles about the rights of workers, which include the just wage. The decision was hailed for protecting businesses, but from a Catholic perspective the economy must serve people, not the other way around.

Catholics are also feminists in our preferential option for the poor and concern for human rights such as health care, education, food, shelter, and protection from violence. Feminists must take Catholic social teaching seriously because women are especially hurt by poverty and the violation of their rights and dignity as human beings.

The U.S. Census Bureau found that the poverty rate of female-headed households was about 30 percent in 2005. Catholic feminists should support an adequate social safety net to protect the health and welfare of women and their children in this country.

Cardinal Renato Martino, the president of the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, recently pointed out that this is an issue worldwide as well: “It must not be forgotten that today extreme poverty has, above all, the face of women and children, especially in Africa,” he said last August.

The United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), aimed at reducing global poverty, identify gender equality (goal #3) and women’s access to employment, education, and health care as economic problems. For those who live on less than a dollar a day—the majority of whom are female—putting food on the table is a women’s issue.

Catholic feminists can act in solidarity with these women by supporting development efforts. Microloans for women, co-ops, and education programs have become key strategies for development because it is now widely accepted that economies grow where women’s conditions improve.

Still, women seeking a better life elsewhere are now half of all migrants worldwide, according to Caritas Internationalis, the Catholic Church’s umbrella humanitarian organization. Caritas focuses on women and migration because women are more vulnerable to exploitation and trafficking than their male counterparts.

Violence affects female migrants, women in war-torn countries, rape victims shunned in their cultures, as well as American women facing domestic abuse and sexual assault. Preventing this violence, in my opinion, is one of the most important causes for feminists. Because each man and woman is made in God’s image, Catholics are called to confront and prevent violence against women wherever it may be.

But what about the elephant in the living room: How are human dignity and respect for the lives of women and unborn children best upheld in the hotly debated area that feminists call “reproductive rights”?

Certainly Catholics and feminists take a variety of stances on the many issues covered by the term reproductive rights: abortion, birth control, sex education, condoms in AIDS-ravaged countries, incest, and rape and its use as a tool of war.

There is some good news on the prickliest of these issues, abortion: A study by Catholics in Alliance for the Common Good found that from 1982 to 2000 benefits for pregnant women, including employment policies, economic assistance, and child care, reduced abortions. These are all women’s issues Catholic feminists can fight for while protecting the unborn.

Being Catholic and feminist isn’t easy, but the important part is that Catholics bring their faith to bear on their feminism, ask tough questions, and act on their beliefs.

When I got angry at my junior high friend for distancing herself from feminism, I’m not sure I could define feminism. In fact, it remains a flexible term covering a large and diverse movement.

But the statement “I’m not a feminist” still irks me. Women and men must look critically at the world, take into account their values, and figure out what it means for them to support the dignity and rights of their mothers, sisters, and daughters.

If Catholics did so, I think everyone would be as proud as I am to say, “I am a feminist.”

Add comment