San Marcos de Tlatazola must have been old when Columbus reached the New World.

Hemmed in on all sides by the cloud-mottled peaks of the Sierra Madre, the village is located in southern Mexico in an arid landscape of few trees, abundant cacti, and an occasional field of spindly corn.

The isolation that for centuries separated San Marcos even from nearby villages has only recently been broken. Just a few miles away, a narrow ribbon of concrete highway runs down the middle of the valley. It leads to Oaxaca, a city of 350,000 where the villagers can buy life’s necessities and sell the red pottery for which they are well known.

The warp and woof, the tapestry that signifies the life of this small community contains signs of contemporary life—the occasional car and TV set—as well as threads and patterns that have endured over the centuries. The people of San Marcos are ardent Catholics, yet they are also apt to cling to their old Zapotec Indian beliefs: The ungainly roadrunner is a source of good luck, the owl brings bad luck, and the butterfly is an ominous sign of death.

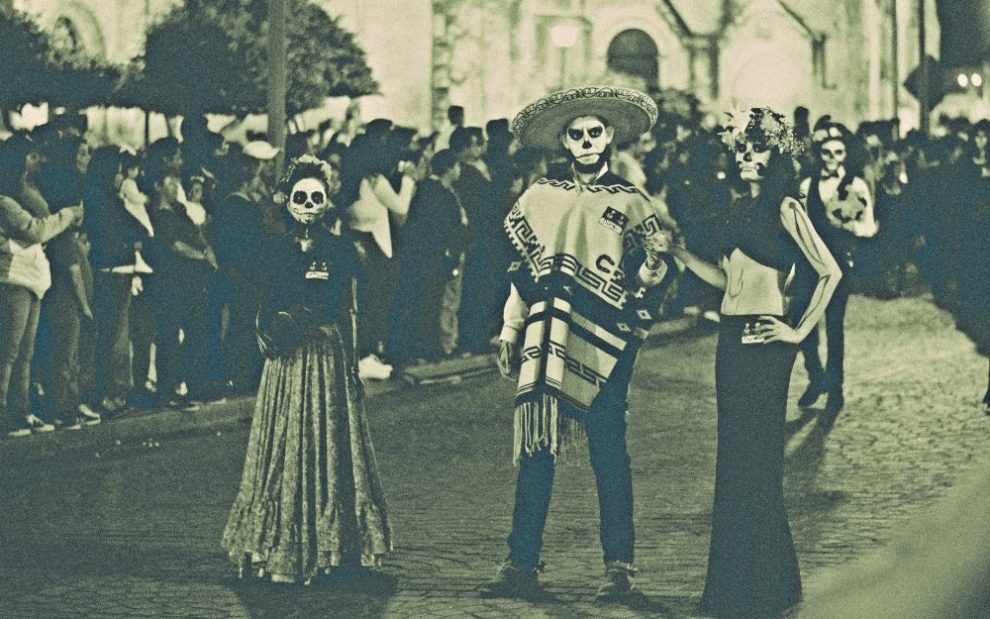

One of the Zapotecs’ most celebrated traditions is that of El Día de los Muertos—the Day of the Dead—the annual holiday, celebrated throughout Mexico, that reunites them with family members and friends who have died.

El Día de los Muertos is a complex mixture of Catholic and pre-Colombian beliefs and rituals. While the actual Day of the Dead is November 2, the festivities start on the last day of October and extend into the first week of November. It is a festival of life, not one of sorrow, because at its core is the belief that a person is not dead until he or she is forgotten, that this life and the next are continuous. It is an expression of our need for transcendence after death.

The people of San Marcos, like all Mexicans, begin the festival by constructing altars in their homes. Some are large and elaborate; others are more modest. They overflow with candles, brilliantly colored flowers, offerings of food and drink, religious icons, and faded photographs of those who are being remembered. A smoldering pot of copal often fills the house with its fragrant aroma.

In cities like Oaxaca these same altars are ubiquitous, appearing in places expected and unexpected: churches, schools, markets, hotels, restaurants, humble shops, large places of business.

El Día de los Muertos is not complete until the living visit cemeteries for contemplative reunion with the dead. Late in the afternoon and evening of the day before this visit, during the waning hours of October, San Marcos’ dusty streets are filled with people carrying candles, flowers, and baskets filled with fruit and bread that will be left as ofrendas—offerings—on the altars of relatives. Because the village is one large, extended family, these visits can number a dozen before the evening has run its course.

At each stop visitors break pan de muerto—bread of the dead—with their hosts and drink hot chocolate and mescal, a potent drink made from the agave plant. In the background, bells in the church fill the night with their melancholy sound.

This article appeared in the November 2001 issue of U.S. Catholic.

Image: Unsplash/Danie Franco

Add comment