On the seventh centenary on the birth of St. Bridget of Sweden, the pope sent a message to St. Bridget’s Order of the Most Holy Savior, praising its foundress as “an example for women today . . . so that they will be protagonists of a society where their dignity is fully respected.”

Intriguing. Who is this St. Bridget, I wondered, who will inspire me to act on behalf of the dignity of women and other excluded groups? How does her story in the 14th century relate to mine in the 21st?

A report from the Catholic news agency Zenit describes Bridget as the daughter of a nobleman, married at age 14, mother to eight children, one of whom became St. Catherine of Sweden. It says she was widowed and eventually founded a religious order, now called the Brigittines.

Hmmm. Daughter of nobility I am not (sorry, Mom and Dad). And I’ve missed the marriage boat by about 12 years so far. Mother to eight? Unlikely (to say the least). Mother of a saint? I’ll do my best. Founding a new religious order is not outside the realm of possibility, though not currently part of my 10-year plan. Thus far I was coming up short on ways to mirror Bridget’s example, and it was still unclear to me how this biography embodied a protagonist for the full dignity of women.

So what did Pope John Paul II mean? I decided to look a little further into the life of Bridget. It turns out that in her stand for equality and dignity for women she was something of a rabble-rouser. Based on direct revelations from God, Jesus, and Mary, she wrote caustic letters to the pope, warning him of the church’s dire state of sin and corruption.

In the 1340s, the pope, Clement VI, was seated in the French city of Avignon instead of Rome, and Rome had fallen hard from its previous glory. Bridget felt that the pope’s absence from Rome was the source of much of the corruption taking place, so she made a pilgrimage to Rome herself to prove her point. She witnessed firsthand the debauchery of the time—how sex, money, and power had made a mockery of the ideals of the church—and thus waged a campaign of public opinion against the pope and his curia.

Eventually, largely due to Bridget’s insistence, the papacy did return to Rome, but only for a short time. In 1370 when Pope Urban V announced his return to Avignon after only three years in Rome, Bridget castigated him, this time through a revelation from the Virgin Mary. Bridget wrote: “What does he do now? He turns his back on me . . . for it wearies him to do his duty, and he is longing for ease and comfort . . . for his own country and his own carnally minded friends.”

Imagine writing such a letter to the pope today!

Bridget warned, “If he should succeed in getting back to his own country, he will be struck such a blow that his teeth will shake in his mouth, his sight will be darkened and all his limbs will tremble . . . and he will be called to account to God for what he did and did not do.”

Imagine writing such a letter to the pope today! Incidentally, the pope did die one month after his return to Avignon.

It almost seems that parts of this letter could have been written by one of today’s victims of clerical sex abuse: “He turns his back on me . . . for it wearies him to do his duty, and he is longing for ease and comfort.”

There are other eerie parallels to the sex-abuse crisis today in Bridget’s writings about the corruption of the hierarchy. Did the pope realize whom he was holding up as a role model for today’s Catholics?

The year 2002, when the pope sent his message, was not a banner year for the church in regard to its treatment of the lowly and excluded—namely children and women. As the sex-abuse crisis makes abundantly clear, too many church officials have exhibited too little concern for anyone but fellow male clerics.

As the sex-abuse crisis makes abundantly clear, too many church officials have exhibited too little concern for anyone but fellow male clerics.

Meanwhile, church officials continue to insist that certain questions involving the role of women in our church are not open to public discussion, nor even to prayerful consideration. Apparently being a “protagonist” for women’s dignity has its limits in our church.

Bridget urged church reform, she cried out ceaselessly against the corruption of the church in Rome, she railed against hypocrisy. And the pope says she’s a model for women today.

So maybe, by the great example of St. Bridget, it is time that I wrote my own letter to the pope.

This article also appears in the January 2003 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 68, No. 1). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

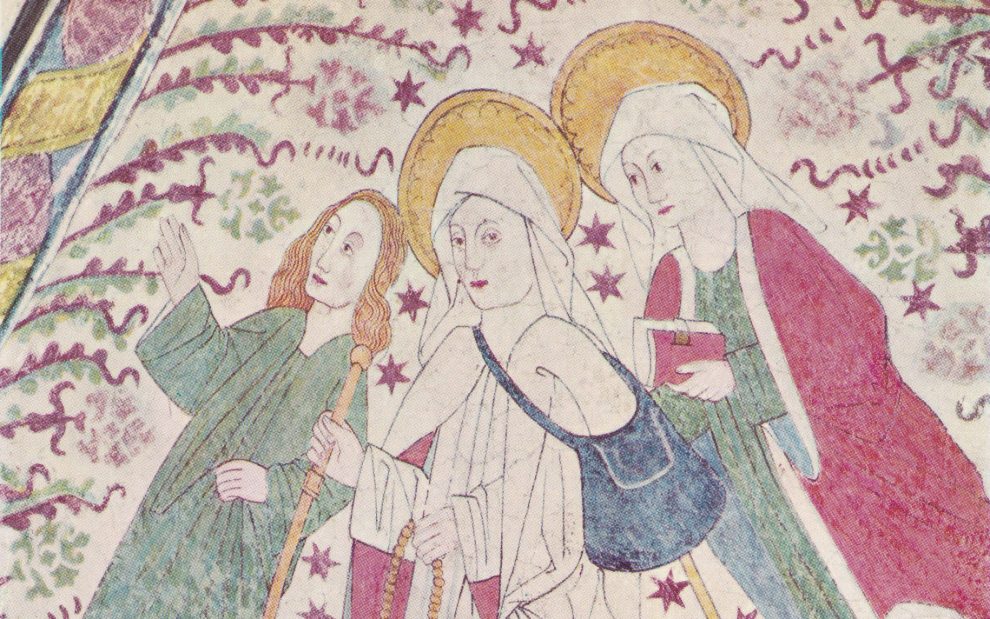

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Add comment