From the era of the catacombs to the present day, Christians have a unique relationship to the art of the image due to the theology of divine incarnation. The belief that God took flesh while remaining fully God and fully human empowers Christians to image the Redeemer without fear of blasphemy.

Throughout history, creators of sacred art have often been eccentric or bizarre, but their work has always gone beyond reflecting their subjective journey to proclaiming the truth of the incarnation. That essential message remains constant within the work, even though sacred art is dynamic and evolves to meet the challenges of every age. The following are just a few of the countless examples of sacred art, both classical and contemporary, that show how an image can move, inspire, challenge, and act as a portal of God’s love and mercy.

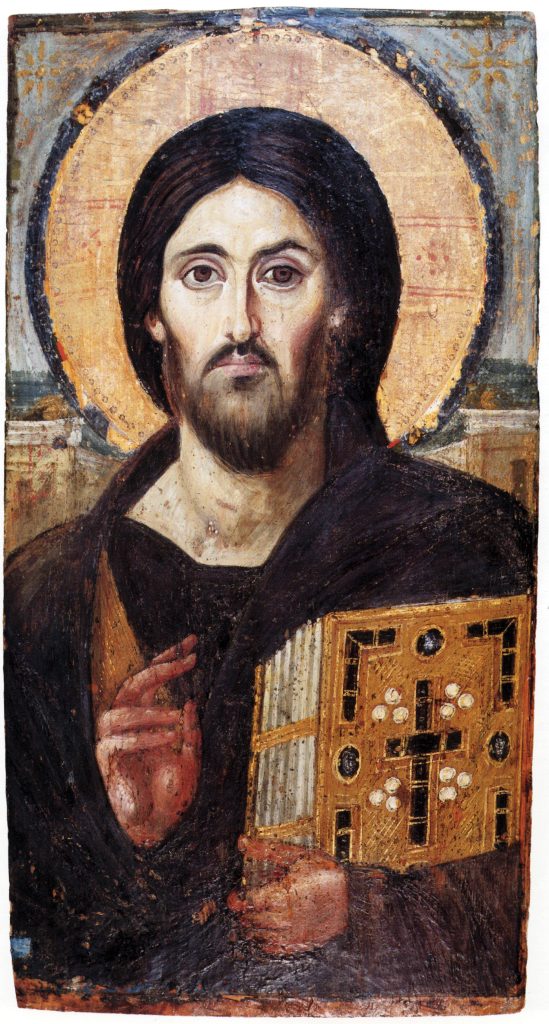

Christ Pantocrator (sixth century)

During a time when disputes over Christ’s divinity and humanity frequently shook the early church, an unknown sixth-century iconographer created a stunning work that proclaims the truth in one timeless and silent image. Painted in encaustic (wax), the icon of Christ Pantocrator establishes the grandeur of Christ as the all-powerful teacher. In the painting, his hand is raised in benediction and he holds the book of the gospels. The question of Christ’s human and divine nature in one person is resolved in the two sides of his face, his dark and shadowed left reflecting the human and the translucent radiance of his right showing his divinity. In one powerful visual manifestation, the imago Dei and verbum Dei are declared as eternally one.

Giotto’s Life of Christ (ca. 1305–1309)

Until the 13th century, much of Western sacred art followed in the footsteps of the Eastern Byzantine style with its ethereal figures and mystical language. While the Italo-Byzantine style of the 12th and 13th centuries achieved a delicate balance between Eastern and Western art, it was Florentine architect and painter Giotto di Bondone (usually known simply as Giotto), along with his master, Cimabue, who began to establish the Proto-Renaissance grammar of Western art. In the Scrovegni Chapel “Life of Christ” and “Life of the Virgin” cycles, Giotto enacts a neologism in sacred art with figures that relate to one another in realistic landscapes with accurate depictions of matter, gravity, and proportion. They are draped in actual fabric and react with recognizable emotions. This art transcends early Renaissance humanism; it makes Christ and the gospel accessible to our common humanity and the real world.

Carravaggio’s The Calling of St. Matthew (1600)

Long thought of as a brilliant but drunken and violent brute, Caravaggio was in fact a devotee of the Counter-Reformation theology of fellow Lombard Cardinal Borromeo. In The Calling of St. Matthew, Caravaggio employs his method of chiaroscuro (“light and dark”) to universalize the call of following Christ in discipleship. The darkly confined space, with a single dirty window leading nowhere, is only illuminated by the blinding shaft of Christ’s presence. The fact that scholars still debate which person in the group is Matthew makes Christ’s call less exclusive and directed to every heart and soul. All are called to holiness and conversion, not in the rarified realms of gold leaf and heavenly choirs but in the dusky muck and confusion of everyday human life.

Giacomo Manzù’s Door of Death (1961–1964)

An Italian communist, atheist, and winner of the Lenin Peace Prize, the sculptor Manzù became a friend of St. Pope John XXIII. Initially, curial officials dismissed Manzù’s bronze Door of Death for St. Peter’s in Rome as too avant-garde, but it is now viewed as a masterpiece of modern sacred art. In a world broken by nuclear war, racial injustice, and colonial oppression, Manzù visually offers people of all faith another way. As the Second Vatican Council was in full motion, Manzù created the doors to reflect death not so much as a mindless and brutal end but as a dignified absorption into the immensity of God’s love. Manzù shows death to be less a dreaded foe and more a portal that eternally unifies us with God and all humanity.

Ioana Belcea’s St. Katharine Drexel (2000s)

Contemporary iconographer Ioana Belcea synthesizes several artistic languages that intertwine in a stunningly original celebration of sanctity and mission. In this large icon installation of St. Katharine Drexel, Belcea draws on the majesty of the Byzantine Pantocrator and the design patterns of Cimabue and Giotto crucifixes to create a modern icon of a very American saint. Drexel’s overwhelming presence is not reflective of her achievements but of her immense love of Christ and the cross above her to which she is obedient. In her portrayal of the Black and First Nation children who were the focus of Drexel’s mission, the textured cloth, and symbols reminiscent of Navajo pottery and petroglyphs, Belcea invokes a sense of inclusivity. Drexel is absorbed into a larger story and her sanctity derives from her Christ-like desire not to be served but to serve.

Wayman Scott IV’s Baltimore Pietà (2022)

Here is the horror of racial violence writ large in stone for all people to see. A visual plea for sanity and tolerance in the face of police brutality toward people of color, Baltimore Pietà uses scriptural imagery to portray the agonizing depths of our common humanity. A Black mother cradles her brutally murdered son, manifesting Mary and the body of her dead son as all the victims of injustice and cruelty in all times. This sorrow is at the heart of the paschal mystery and evokes the moment when the young Elie Wiesel saw a boy executed in a concentration camp. When someone asked, “Where is God?” Wiesel heard within the whispered response: “He is there, hanging on the gallows.”

For two millennia, Christians have had both the privilege and the invitation to preach the gospel to the whole world. Evangelization, like the art discussed here, takes many forms but always points to the truth of Jesus’ incarnation and the work of salvation. Of all called to proclaim the Good News of God’s love and mercy, artists may be the ones who can do so in the most original and creative ways.

Artists like architects, musicians, writers, and poets draw from the past as they move forward, proclaiming what is ever ancient in voices that are ever new. We grope, we stumble, we try, we fail, and we try again in aiming to express visually what is believed within. Perhaps a good guiding light is the maxim scribed by the brilliant French art critic André Malraux (ironically, also an atheist) in his magisterial history of art, The Voices of Silence. Malraux wrote that only sacred art need not be contextualized in a certain space to have spiritual resonance, because only sacred art is never decontextualized.

This article also appears in the February 2024 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 89, No. 2, pages 20-24). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Add comment