Interestingly, but perhaps not surprisingly, only 42 percent of the population surveyed in a Pew Research Center poll responded that being part of a Catholic parish is an essential part of what being Catholic means to them. What were once epicenters of local faith activity—including catechesis, reception of the sacraments, and even social life—have become seemingly unnecessary in the lives of many Catholics today. For those actively involved in parish life, especially parish ministers, this reality is sobering. We might instinctively attribute this to any number of recent events in our church and world—clerical abuse, church teaching on sexuality, increasing political polarization, just to name a few—but perhaps the reasons themselves are not as telling as we might like to imagine.

Whether or not this resonates with our own empirical and anecdotal experience, if we set these assumptions aside, we can instead focus on another interesting finding from that original Pew survey: A third or more of cultural Catholics say they observe Lent, go to Mass at least occasionally, and would want the sacrament of the anointing of the sick if they were very ill. (In this study, “cultural Catholics” do not identify Catholicism as their religion but do identify as Catholic.) Cultural Catholics find something appealing or important about some of the fundamental elements of parish life, namely liturgical prayer and sacraments.

Liturgical prayer, including the celebration of the sacraments, can be the starting point for parish revival, if we allow it. In 1964, in response to growing individualism in the church and world, Italian liturgical scholar Romano Guardini asked a critical question: Is it possible for 20th-century Christians to engage in worship? His two-fold answer was simple. If people of the modern world are to authentically engage in worship, they must be willing to perform communal acts and let ritual speak for itself, uncluttered by unnecessary words. Liturgical acts are not superfluous, but essential.

If the COVID-19 pandemic has taught us anything, it is that we cannot exist as isolated individuals. It is impossible to separate ourselves from others, no matter how hard we try. This fundamental interconnectedness, or solidarity, is part of being human. We might say that our personal choices do not affect others, but we have come to learn this is entirely false. We might argue that our individual actions do not affect those of our neighbor, but this is both inaccurate and, frankly, selfish. This is especially true in an ecclesial context. We cannot privatize our life in Christ. This is one of the reasons I become increasingly frustrated when I hear people say that sacraments should be private events.

I grew up on the South Side of Chicago where baptisms, weddings, and anointings were family affairs. Of course Grandma and Grandpa and aunts and uncles and cousins would participate in the celebration, but to even think about celebrating those events with the larger parish community would be laughable. It was my cousin’s baptism. It was my aunt’s wedding. It was my grandmother’s anointing. It wasn’t until I started teaching sacramental theology that I explored the text of the rites themselves and began to understand that these occasions in the church are not personal events. Rather, they are robust important elements of a healthy parish community.

The Order of Baptism of Children begins with this explicit instruction: “Baptism should be celebrated, insofar as possible, on a Sunday, the day on which the Church recalls the Paschal Mystery, and indeed in a common celebration for all the newly born, and with the attendance of a large number of the faithful, or at least of the relatives, friends, and neighbors, and with their active participation.” In this rich introductory statement, we note several important instructions for the celebration of baptism. Baptism should be celebrated on Sunday, with other children, and with “a large number of the faithful” actively participating.

Like all liturgical celebrations, the celebration of baptism is a public and communal act. While there are circumstances where this may not be possible, these should be considered the exception and not the norm. In Luke’s account of Jesus’ baptism, the evangelist notes the presence of the community: “Now when all the people were baptized and when Jesus also had been baptized” (Luke 3:21). Even Jesus’ own baptism was not a private event.

It seems surprising then that so often the baptism of children has been reduced to an individual family celebration, separate from the rest of the Christian community. While the family of course represents the greater community, there is something lost when the communal aspect of the sacrament is not exercised. Life in Christ is deeply communal. We do not and cannot exist as isolated individuals, despite our best efforts to do so. Consider the opening greeting from The Order of Baptism of Children. In addressing the parents and godparents, the celebrant explicitly names the importance of the larger Christian community:

“Dear parents and godparents: Your families have experienced great joy at the birth of your children, and the Church shares your happiness. Today this joy has brought you to the Church to give thanks to God for the gift of your children and to celebrate a new birth in the waters of Baptism. The community rejoices with you, for today the number of those baptized in Christ will be increased, and we offer you our support in raising your children in the practice of the faith. Therefore, brothers and sisters, let us now prepare ourselves to participate in this celebration, listening to God’s Word, praying for these children and their families, and renewing our commitment to the Lord and to his people.”

This is not just limited to baptism. The communitarian character of the sacraments of matrimony and anointing of the sick is essential, and both may take place during Sunday Mass. The Order of Celebrating Matrimony notes, “Since Marriage is ordered toward the increase and sanctification of the People of God, its celebration displays a communitarian character that encourages the participation also of the parish community, at least through some of its members. With due regard for local customs and as occasion suggests, several Marriages may be celebrated at the same time or the celebration of the Sacrament may take place during the Sunday assembly.” Likewise, Pastoral Care of the Sick (in which we find the rite for the sacrament of anointing), states, “Because of its very nature as a sign, the sacrament of the anointing of the sick should be celebrated with members of the family and other representatives of the Christian community whenever this is possible. Then the sacrament is seen for what it is—a part of the prayer of the church and an encounter with the Lord.”

Sure, celebrating a baptism or a wedding or an anointing during Sunday Mass will inevitably lengthen the liturgy a bit. But the ritual of liturgical prayer is powerful, even transformative. Rather than hurrying up to get through the Mass, what if we spent time celebrating and savoring the richness of the sacraments, not as isolated individuals but as a unified and united parish community?

We would do well to revisit Guardini’s question from 1964 today. Can liturgy mean anything for 21st-century Christians? I believe we need to answer the question in the same way Guardini proposed more than 50 years ago. People need to see new members join the church and intentionally work to welcome them. People need to see the love embodied by a couple and allow that love to spill over into their own lives. People need to see the healing presence of Christ in those who are ill and recommit themselves to caring for these members of the community.

Liturgy will mean something if we dare to celebrate sacraments communally and allow the rites and symbols—the water, the witness, the oil—to penetrate our hearts and transform us into whom we are called to be. There is no doubt that the abuse crisis and lack of trust of religious leaders, the seemingly cold social stances of the church, and the weekly lackluster preaching and bad music all contribute to a decline in the vitality of parish life. But we cannot respond with lament and nostalgia. Rather, we must be bold enough to celebrate the richness of the sacraments in the context and manner in which they are intended.

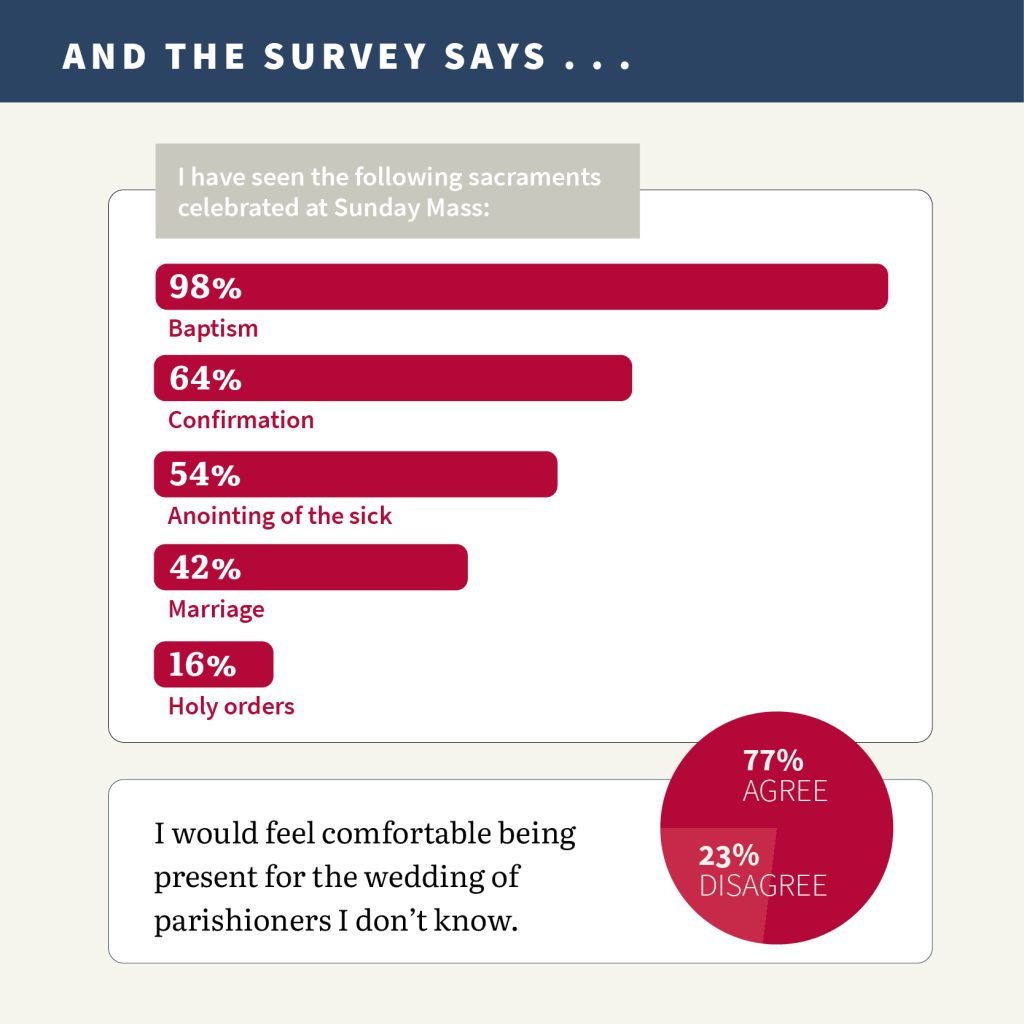

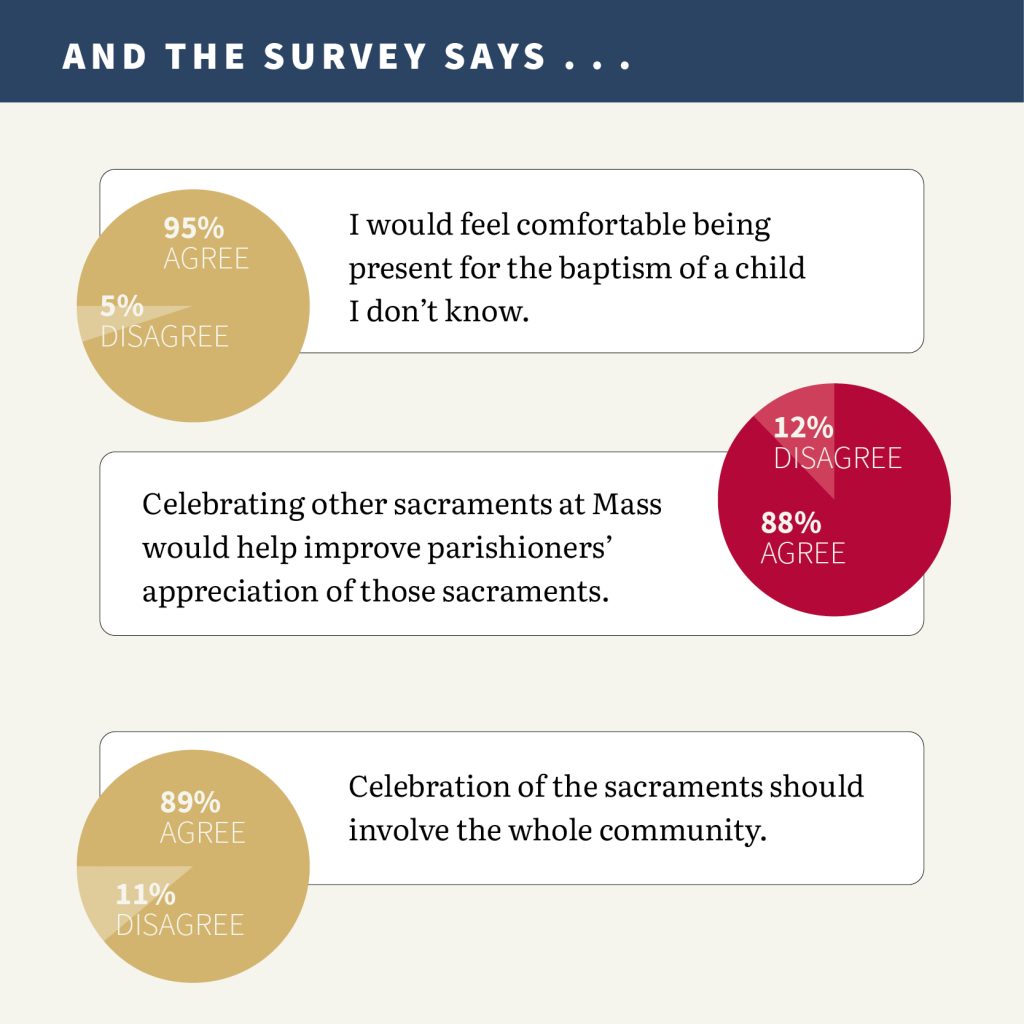

Results are based on survey responses from 178 uscatholic.org visitors.

This article also appears in the August 2023 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 88, No. 8, pages 21-35). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Shutterstock/Zvonimir Atletic

Add comment