Jesus never missed an opportunity to turn a meal into a meaningful encounter. He had a deep awareness of the transformative capacity of sharing food. Some of the great “food films” dialogue easily with the many meanings of his meal sharing, from the way he offered relationship through food sharing, to his self-giving Last Supper, to the heavenly banquet his meals foreshadowed. Here is a sampling of a few such food films.

Food as relationship

Many food films feature sumptuous imagery of food preparation and mouthwatering servings. The best also underscore the offer of relationship at the heart of a meal. Films such as The Hundred-Foot Journey (2014) and Chef (2014) dramatize this well. Yet any list would be incomplete without the paradigmatic Eat Drink Man Woman (1994), which features an aging chef making one monumental family feast after another for his three adult daughters as his own tastebuds fail.

Food seems to be the only love language he knows, but when he prepares so much that there’s no room at the table for anyone else’s contribution, relationships become strained and food can lose its flavor. In his book Ministry at the Margins (Orbis Books), theologian Anthony Gittins keenly observes that Jesus modeled how to be both a good host and a good guest. Each are essential. True relationship is about being able to receive as generously as one gives, and Eat Drink Man Woman portrays this in lavish fashion.

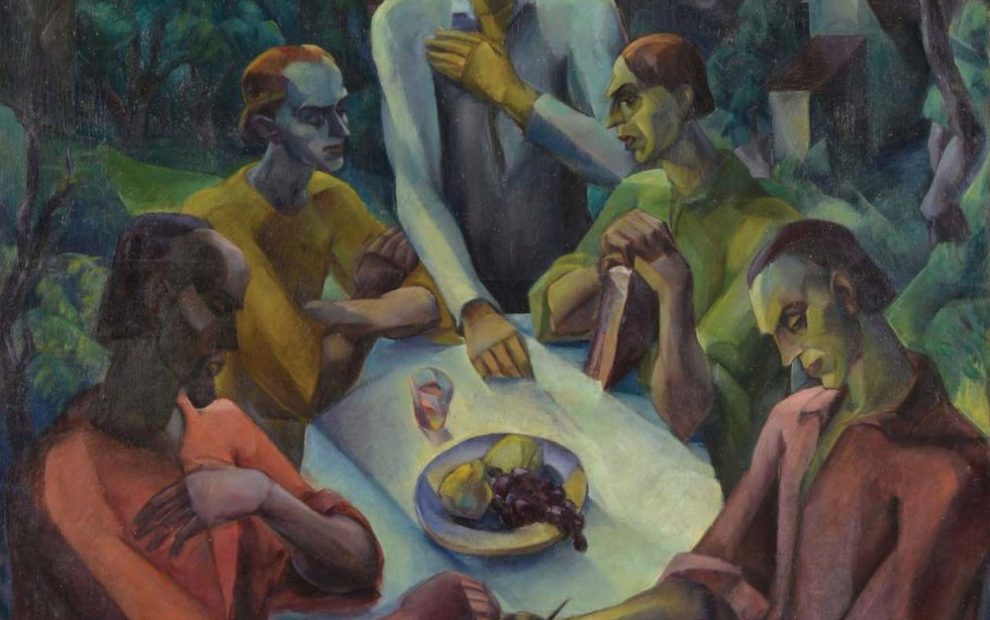

Last suppers

We don’t necessarily know which meal will be our last, but sometimes a person can sense it. Sensing that our time is limited can remove the veils from our eyes. A “last supper” of this sort has transcendent possibilities and the potential to change hearts. Of Gods and Men (2010) tells the story of a group of Cistercian monks situated in a small village in Algeria. While the townspeople greatly value the monks’ presence, especially the medical clinic staff, political unrest in the country brings violence and terrorist threats.

At first glance, one might not consider this a food film as much as a film about conscience, solidarity, and Christian witness. Looking closer through a Catholic lens, the monks frequent table gatherings, especially as they celebrate the Eucharist. These gatherings powerfully portray how breaking bread together in a time of crisis can not only hold a community together but also provide the grace to face another day. When they unanimously decide to stay, one of them declares, “Let God set the table here. For everyone. Friends and enemies.” Sensing it could be their last supper, a monk helps temporarily alleviate their fears and transcend the moment with the unexpected gift of Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake and a modest sharing of wine.

The shadow of death hangs heavy in the acclaimed film Tangerines (2013). The film centers upon two Estonian men, Ivo and Margus, who are caught in the middle of a war in Abkhazia, Georgia. While other Estonians flee, they stay to harvest and pack their crop of tangerines. The war literally arrives at their doorsteps when they hear explosions and gunshots. They discover in the wreckage of smoldering vehicles several dead soldiers and two wounded survivors, Ahmed and Nika. Ivo takes them into his home and tends to them. In the process the two opposing soldiers are confronted with each other’s presence. Ivo convinces both to agree that while they are in his small home they will not kill each other. Ivo navigates the difficult conversations and tense moments, offering the wisdom of someone who has already lost a son to war.

Impressively, these exchanges often happen around the kitchen table, where Ahmed and Nika are forced to eat together. Over the course of a few meals, heated exchanges, threats, and unexpected storytelling, each man begins to see the other in a different light. The juxtaposition of war, violence, and death with a plentiful grove of fruit trees provides an evocative visual contrast. Can they be “fruitful” and “life-giving” like the orchard, or will the possibility of peace wither and die on the branches? Through Ivo’s quiet and dignified witness, the film is a profound message about the value of hospitality and who we welcome to our table.

A foretaste of the heavenly banquet

No Catholic food film discussion would be complete without Babette’s Feast (1987). In fact, it is the pièce de résistance, or, perhaps more appropriately, the “Cailles en Sarcophage” of the visual banquet. The story begins in tragedy when a bedraggled Babette Hersant arrives in a small, austere Danish village, where two women take her in. We learn she has fled France where her husband and son have been killed in a revolution. The women are the daughters of an influential, puritanical pastor who had inspired a Christian congregation, but years after his death the community has lost its way. Going through the motions, they have given way to bickering, barbs, and grudges. Babette’s unique ability to turn the simplest fare into something to be thankful for seems to be their silver lining.

When Babette wins a lottery and asks permission to prepare a feast for the small congregation, they are skeptical but cannot turn down her gracious offer. They decide to eat the meal without enjoyment, in a spirit of detachment. Babette, who we discover is a famous French chef, makes an unparalleled five-course meal. Through her abundant gift and the fortuitous visit of an old general who voices his amazement over the quality of the meal, the small community begins not only to enjoy the food but to reconcile and discover new possibilities.

Ronald Rolheiser, in his popular book The Holy Longing (Image), observes that there is no Easter resurrection without the suffering, death, and mourning of Good Friday. New life is possible, but death and grieving must precede it. Poor Babette has lost her family and the ability to express her vocation as a chef. The sisters and members of the community all have their own losses, failed dreams, and deaths. Babette’s feast brings her the gift of new life, stirs hearts to seek reconciliation, and restores the entire community. It is a resurrection and a heavenly feast.

This article also appears in the July 2022 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 87, No. 7, pages 21-22). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Wikimedia Commons/ The Last Supper, Gyula Derkovitz, 1922

Add comment