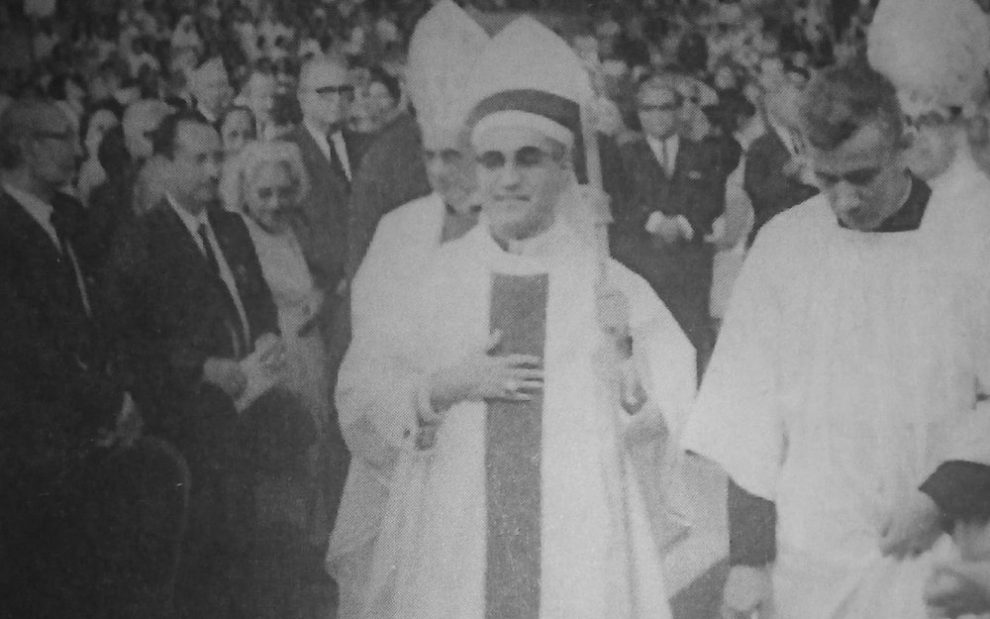

In the throes of the Salvadoran Civil War, St. Archbishop Oscar Romero was murdered because he stood with his people against oppression. Prior to his death, most of his fellow bishops decried his efforts, accusing him of succumbing to popular pressure and becoming “politicized.” As Renny Golden detailed previously in U.S. Catholic, “The poor never expected him to take their side and the elites of church and state felt betrayed.”

We celebrate Romero’s feast day on March 24, and we can learn much from his commitment to living life attuned to the poor, as Jesus did, and from his willingness to call out the church when it failed to bear authentic witness to the Kingdom of God. As Catholics navigate contemporary culture wars in the United States, the theology of liberation espoused by Romero (among others) offers important insights.

Most readers will be familiar with the “preferential option for the poor,” which maintains that our social and political activity should prioritize the needs of the poor and vulnerable. Liberation theology expands this principle: because, Jesus said, we will meet Christ through encountering our marginalized brothers and sisters, the experiences of the oppressed are profoundly significant to the Spirit’s movement in history and should be affirmed and incorporated into our theological awareness. Those of us with privilege are called to radical accompaniment of those who have been marginalized—to hear their appeals for justice and to walk with them in their struggle for full participation in social, political, and ecclesial life.

In this light, as we attempt to respond faithfully to contemporary issues, we should prioritize the voices of those who experience poverty of influence. Insofar as Western social norms were developed according to a Christian framework—interpreted primarily through a white, male lens that deliberately excluded the influence of most others—the preferential option should inform Catholic responses to people whose personal pursuit of integrity appears at odds with these norms. Liberation theology highlights the need for humility as we encounter divergent views and an openness to the transformative grace experienced through them.

Indeed, liberation theologian Diana L. Hayes reminds us that “theology emerges from a people’s efforts to understand themselves in relation to God. Yet God is always and everywhere incomprehensible mystery. As St. Augustine realized, if we have understood, then what we have understood is not God.” When it comes to applying eternal truths to temporal realities, then, different interpretations are to be expected. This is not to say that there is no truth beyond personal experience—only that as we attempt to live out what we believe to be true, we should recognize that we are inevitably missing something of the divine. Romero, too, emphasized that “given our limitations, the truth is always the concrete expression of a person who has a particular style and a way of being.”

When there are voices that challenge our understanding of who God is and the moral and political obligations that derive from this understanding, it is important to grapple with those challenges with, as the Psalmist writes, a “contrite heart and a humble spirit.” Sister Thea Bowman once lamented that when Black Catholics “attempt to bring our blackism to the church, the people who do not know us say that we are being ‘non-Catholic’ or ‘Separatist’––or just plain ‘uncouth.’” Rather than denying the relevance or authenticity of diverse voices, we should delight in hearing the perspectives of others and incorporating their experiences into our awareness of God. This is why Pope Francis urges us to “stay close to the people” as we work for justice.

Our aim is not only to convert others but also to be converted ourselves.

––Oscar Romero

Importantly, in the work for justice, liberation theology focuses our attention on social sin. As Romero put it, the gospel must “touch the real sin of the society in which it is being proclaimed.” Though personal sin and social sin are interconnected, the urgency of political engagement stems from the realities of those who have been made vulnerable through unjust and exclusive social structures. This lens requires us to take seriously accusations that our faith is fostering oppression or discrimination. And if it turns out that a political approach that privileges the voices of those on the margins in fact leads to the oppression of Christians (an historically privileged group in the United States), then we can advocate for justice based on those new empirical realities.

Romero certainly knew what it was to experience religious persecution, but he explained it thus: “The church suffers the fate of the poor, which is persecution.” Catholics, then, should be concerned primarily with the persecution that arises from identifying with the marginalized, rather than aligning with those in power and assuming a kind of false victimization. As theologian M.T. Davila writes, “the preferential option [for the poor] inherently orients discipleship toward the marginalized and victimized other and her or his life experiences, and yet a culture of privilege turns the person inordinately toward the self.”

If our faith is authentic, its beauty will attract our neighbors toward fullness of truth; but encounters with others should expand our moral vision, too—the gospel should “get under our skin!” As Romero asserted with his fellow bishops, “Our aim is not only to convert others but also to be converted ourselves … so that our dioceses, parishes, institutions, communities, and religious congregations are not obstacles but rather incentives for living the gospel.”

This approach to living our faith requires dialogue that recognizes the equal dignity of every person and fosters the love that should ground all activity—a love that is not permissive, but that nevertheless is fundamentally about “letting [the beloved] be,” as John Dool (following Augustine) puts it. Here, we can learn from Romero, who declared, “I don’t want to be an anti, against anybody. I simply want to be the builder of a great affirmation: the affirmation of God, who loves us.”

Rather than obstinately arguing “against” those who offer diverse perspectives, then, we should prioritize input from the voices that we have ignored or misunderstood.

Advertisement

Life, and the struggle to live as an integrated self, is a grace-filled journey for each of us, and as we encounter others along the way, we should recognize in them the Incarnate Christ. Indeed, as Hayes writes, “It is … experience which also interprets the meaning of Christ as God’s revelation today. For God is always present in human experience.”

Rather than obstinately arguing “against” those who offer diverse perspectives, then, we should prioritize input from the voices that we have ignored or misunderstood, especially those who have been excluded from participating in the development of Catholic moral teaching. As we seek to live out our faith in public life, we should adhere to Sister Thea’s wisdom: consider ways to “work together so that all of us have equal access to input—equal access to opportunity—equal access to participation. Go in the room and look around and see who’s missing and send some of your folk out to call them in so that the church can be what she claims to be—truly Catholic.”

In this way, we can begin, as Romero urges, to “truly live the beauty and responsibility of being a prophetic people.”

Image: CC Wikimedia Commons/Tenquique503

Add comment