When I was a junior in high school—a Catholic, all-girls school—I advanced to the regional round of the state science exposition. My parents drove me to Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry where I set up my meticulously decorated trifold project board and sat beside it for five hours. The judges came and went, and I gave my spiel. Occasionally a judge would notice I attended an all-girls school, say something like “girl power!” and comment on how my status as female and my apparent science aptitude was encouraging for women everywhere. Excelling in a STEM field (science, technology, engineering, and math) was a great feat! You were a special girl if you did STEM.

The truth, however, is that I was not a STEM girl. While I liked my biology and geometry classes, I was more interested in writing and art. But, often in the name of defying gender norms, I was regularly encouraged to explore STEM. I remember my guidance counselor suggesting I become a science textbook writer when I told her I wanted to major in English and journalism in college. At last, a useful application for my writing hobby! Even now, with a day job in journalism, I’m still encouraged by industry professionals to become a journalist who can code.

As frustrating as it is to be told my career would be worth more if it involved technology, my beef is not with STEM itself. I understand the need for such education, and girls who have genuine or developing interests in these fields should absolutely cultivate their skills. But pushing girls into STEM teaches them that men set the bar—and runs counter to what all-girls schools do best.

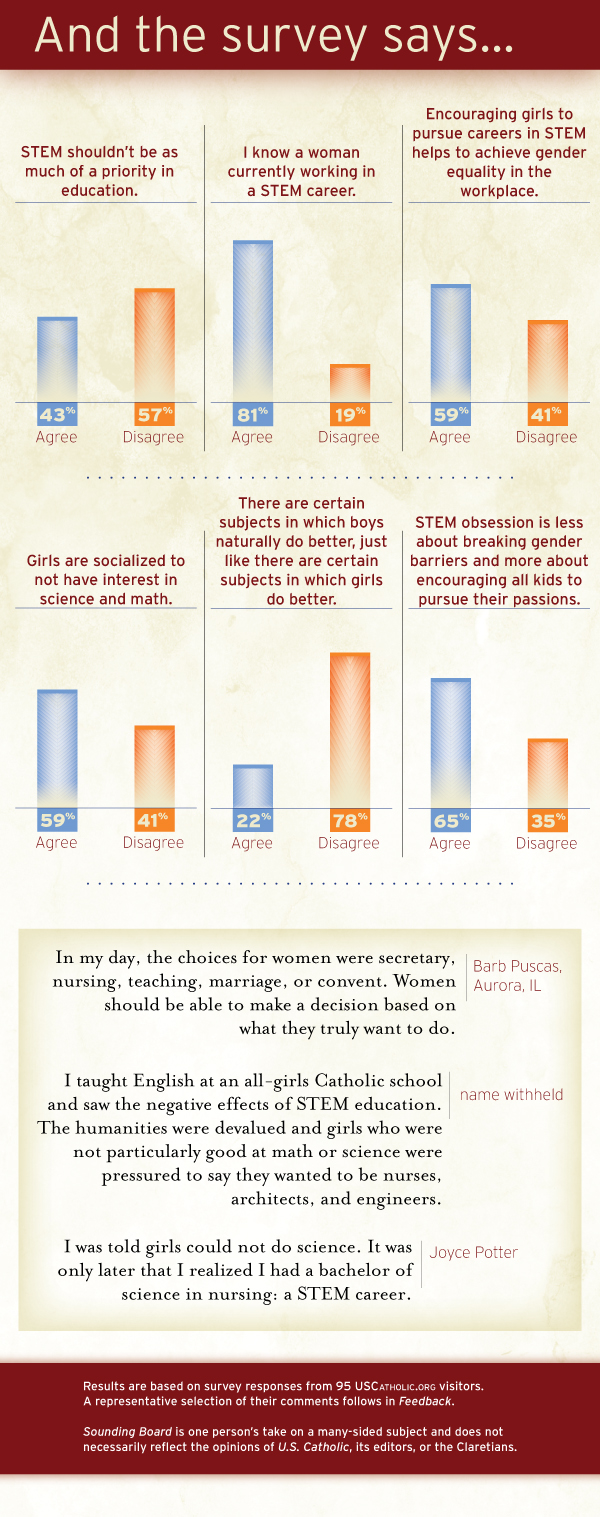

Denise Cummins, a research psychologist and fellow of the Association for Psychological Science, writes that two universally accepted “truths” are that men outnumber women in STEM fields, and that women are socialized to avoid STEM fields as career choices because society considers them “unfeminine.” This has spawned a national effort to attract girls and young women into STEM, and the preferred strategy, she says, is to attract females by “unbrainwashing them” into accepting that STEM careers are not just for men.

Studies actually indicate the STEM gender gap is pretty overblown. According to National Science Foundation statistics, there’s no gender difference regarding undergraduate degrees earned in the biosciences, the social sciences, or mathematics, and not much of a difference in the physical sciences. And of the top undergraduate STEM programs in the country, most have male-to-female student ratios close to 1:1.

Even so, the “unbrainwashing” attempts are superfluous. Just recently I received an alumnae newsletter that detailed all of my alma mater’s new STEM achievements: course offerings, a fancy STEM lab, some sort of robotics award, and 10 different STEM-related clubs. My school isn’t alone; the White House has a “Women in STEM” initiative, a Catholic high school in Kentucky recently became the first all-girls school with a certified STEM curriculum, and the Los Angeles Unified School District has opened two all-girls STEM schools. A company called GoldieBlox has even started making building toys pink and princess-themed so more girls will play with them.

With so much national attention on the subjects, it makes sense all-girls schools would be proud of their STEM offerings. For instance, the National Coalition of Girls’ Schools (NCGS) proudly highlights three statistics on their website:

• When rating their computer skills, 36 percent of graduates of independent girls’ schools consider themselves strong students, compared to 26 percent of their co-ed peers.

• 48 percent of girls’ school alumnae rate themselves great at math versus 37 percent for girls in co-ed schools.

• Three times as many alumnae of single-sex schools plan to become engineers.

As encouraging as the NCGS-touted statistics are, the best thing about all-girls schools isn’t STEM achievement. It’s that girls achieve everything. Girls are the gym class team captains, the science fair winners, the school newspaper editors. They make up the entire student council. Gender bias never enters any classroom or any subject. Perhaps this unbiased environment is why all-girls school students have confidence in their skills and explore STEM fields to begin with. The girls who like STEM are already there, and the ones who aren’t don’t need an extra push.

And pushing stereotypical “boy subjects” on girls is a regressive approach to achieving gender equality. The push only reinforces the gender norms all-girls schools have the opportunity to overthrow. The idea that schools need to somehow make girls interested in STEM (imagine school campaigns aimed at making more boys interested in nursing or teaching) reaffirms the social narrative that STEM is a prestigious boys’ club that girls must break into and that a girl’s intelligence is only validated once she excels in one of the more complex “boy subjects.”

If, hypothetically, men suddenly outnumbered women as preschool teachers, would campaigns exist encouraging women to explore early childhood education? Probably not. This is because the STEM obsession is less about equality and more about masculinity.

In her blog Lady Economist Kate Bahn writes, “I sometimes wonder to what extent my desire to be taken seriously, like one of the boys, played into my decision to become an economist over, say, a sociologist. . . . And what does it say about me, as a staunch feminist, if I’m relying on masculinity to convey my worth?”

The underlying belief, whether STEM advocates realize it or not, is that traditionally male-dominated fields are more valuable to society than those that have traditionally appealed to women. A study published in the Oxford journal Social Forces even shows that a field’s overall pay drops when women enter it in greater numbers. (Biologists’ wages, for instance, fell by 18 percent when this happened.) Society simply undervalues jobs once women start doing them.

Author of In Defense of a Liberal Education Fareed Zakaria writes that in recent years public officials have cautioned against pursuing degrees like art history (the stereotypical “women’s degree”), which are seen as expensive luxuries.

Is my job at a magazine an expensive luxury? It may pay less than careers in STEM. But, for me, any reason I considered a STEM career didn’t come from an innate interest in science but rather a desire to prove myself. The belittling of “woman degrees” encourages women to venerate men and can drive women who are genuinely disinterested in STEM into the wrong careers.

Louie Cronin, who produced the long-running public radio show Car Talk, recently wrote about how she and her Public Radio International colleagues aired a series of interviews that encouraged young women who liked math to go into engineering. She later wrote about the series, saying that in college she “fell for the advice” and pursued engineering because she was good at math—even though she knew she wanted to work in radio.

“I worry about all this pressure on girls to go into the STEM fields,” Cronin writes. “Girls should find out what they love and go into that. If it’s engineering, fine. Let’s break down the walls, remove all gender barriers, give them the math skills they need. But please, don’t push them.”

All-girls schools have a unique opportunity to do this. And this opportunity is exactly why all-girls schools should be wary of America’s obsession with STEM education, as it challenges the very thing these schools do best: teach young women that men never set the bar.

This article also appears in the September 2016 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 81, No. 9, pages 17–21).

Image: Flickr cc via USAID Asia

Add comment