In 1990, as the country prepared to celebrate the 500th anniversary of the arrival of Christopher Columbus, something in Father John Giuliani’s heart recoiled. His knowledge of the violence, suffering, and oppression the Native American peoples endured contrasted sharply with the upcoming national celebration of European “discovery” of the Americas. But what could he do? As an artist, priest, and person of Italian descent, he wanted to do something to make his own personal reparation for the atrocities of the past.

Father Giuliani threw himself into creating paintings that celebrated the lives and cultures of indigenous peoples. A classically trained iconographer with a great love for beauty, a meticulous eye for detail, and a researcher’s disposition, he quickly produced 22 pieces of art over the course of a year. These works not only sparked a wave of critical interest in his art but also encouraged him to dive deeper artistically and spiritually into an unfamiliar worldview—one predating the arrival of Christianity in the United States.

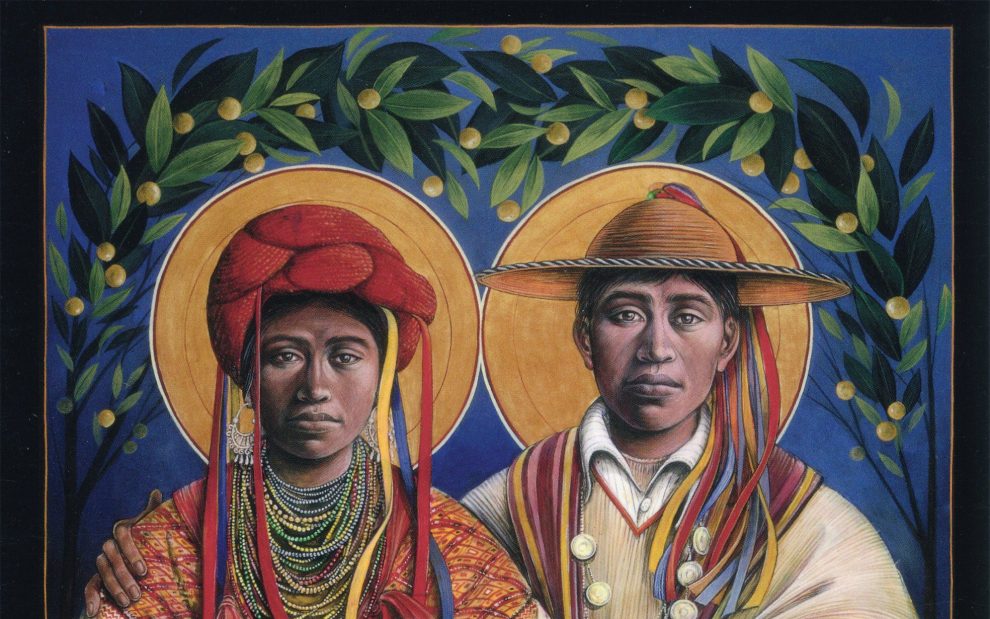

Giuliani’s obvious deep respect for the people he depicts and distinct iconographic style offer audiences a glimpse into a spiritual perspective that, while different from European Christianity, has much to teach audiences about our relationship to God. While technically impressive, his art also expresses a love for Native American peoples and their own artistry, which comes to the fore in each of his paintings. One has only to gaze upon the masterful Marriage of Mary and Joseph to recognize Giuliani’s tremendous admiration for the Native American peoples and their cultures. Each flower petal, ribbon, and fiber is carefully rendered and woven into a harmonious whole. The painting celebrates Mary and Joseph’s openness to God’s unfolding plan of salvation and honors how the tribe’s culture memorializes such commitments.

There is a deep convergence of spiritual kinship between Giuliani and the people he depicts. His paintings draw on Christianity and Native American spiritualities to show how closely some of our commitments parallel. For example, he draws on both biblical accounts of God’s relationship to creation and the Native American concept of “grand ecology.” Prolific orange trees burst with fruit as they frame Mary and Joseph at their wedding. A youthful holy family is completely integrated into their natural environment, surrounded by lush foliage. These common threads of religious experience can also be seen in Giuliani’s penchant for reenvisioning classical religious motifs—whether the annunciation, images of the Madonna and child, or depictions of angels and popular saints.

Native Americans and their way of life have all too often been marginalized—both in the past and in the present. Giuliani’s work brings a much-needed celebration of these cultures to the public eye, showing us the beauty in ways of life besides our own. His work destabilizes our image of saints and other religious figures as people who look like and reminds us that there is truth in other religions, cultures, and histories. It also reminds us of the true meaning of the incarnation: God, sent down in human form to save us all, regardless of our skin color, culture, or religion.

Guatemalan Mother and Child

Giuliani’s characteristic style can be described as a hybrid between Orthodox iconography and Italian Renaissance naturalism, both employed to celebrate and honor indigenous peoples. His Bolivian Saint Christopher and Guatemalan Mother and Child are exceptional examples. With their centralized figures, solid colored backgrounds, and golden halos, both paintings evoke the Orthodox icon tradition without slavishly following its strictures. The gentle, affectionate glances and gestures between the figures, paired with how realistically each person is painted, call to mind the style of Renaissance masters like Fra Angelico and his contemporaries.

As Fra Angelico did before him, Giuliani explores the theme of the Madonna and child in numerous paintings. The vulnerable, inquisitive Christ-child lovingly wrapped in his mother’s protective and supportive arms finds abundant variations in Giuliani’s art. The difference between Giuliani’s work and that of Renaissance painters is in the form these variations take. For artists like Fra Angelico, any distinctions between paintings are largely decorative. However, Giuliani’s variations are cultural.

Giuliani paints the Madonna and child as members of the Hopi, Potawatomi, Choctaw, Cheyenne, and Seminole tribes. Multiple cultures receive their own personal representation of the Blessed Virgin Mary and her beloved son Jesus. Adorned in meticulously rendered patterned blankets and embellished with culturally specific and significant colorful beads, Giuliani’s variations are reminiscent of the famous image of our Lady of Guadalupe; the painting shows that every human being can be an image of holiness and divinity. Furthermore, they emphasize Mary and Jesus as human, aligned with each of us in our own cultural and historical specificities.

Giuliani recounts a specific occasion when he deeply felt the effect of his work. A Native American woman viewing Giuliani’s Mother and Child painting began to weep. She told him that she wept because, for the first time, she saw herself and her people represented as the Madonna and child instead of Europeans. Such a visual display of solidarity was, and is, profoundly moving. However, these images are about more than solidarity; they illustrate the full meaning of the incarnation. God did not come merely to Europeans, but to all.

Joseph’s Dream (Guatemalan)

This mysterious midnight blue and sunset yellow painting is one of Giuliani’s most inspired works. It portrays the unfolding drama of Mary and Joseph’s wedding in a Guatemalan setting. The almost lyrical composition makes no distinction between reality and dream or human plane and divine sphere; angel, saint, and dream all occupy the same flat space and are depicted in equal detail and style. We are being visually assured that all the painting’s content is real. The angel and the angel’s message are just as visually “true” as Joseph. Thus the painting itself echoes the angel’s message: “Have no fear.” God’s word is trustworthy.

Beyond this, the painting itself is simply a joy to behold. The vivid color palette and the mantel of blossoming orange trees—even the fact that Joseph is wearing sneakers—add a delightful, whimsical component. Here Giuliani seems to have intuited that same, almost magic realism that informed Frida Kahlo, yet without the tragedy or more oblique surrealist elements that shaped her work. Joseph’s Dream proposes that wonder can be brought forth from challenging circumstances and dreams can come true.

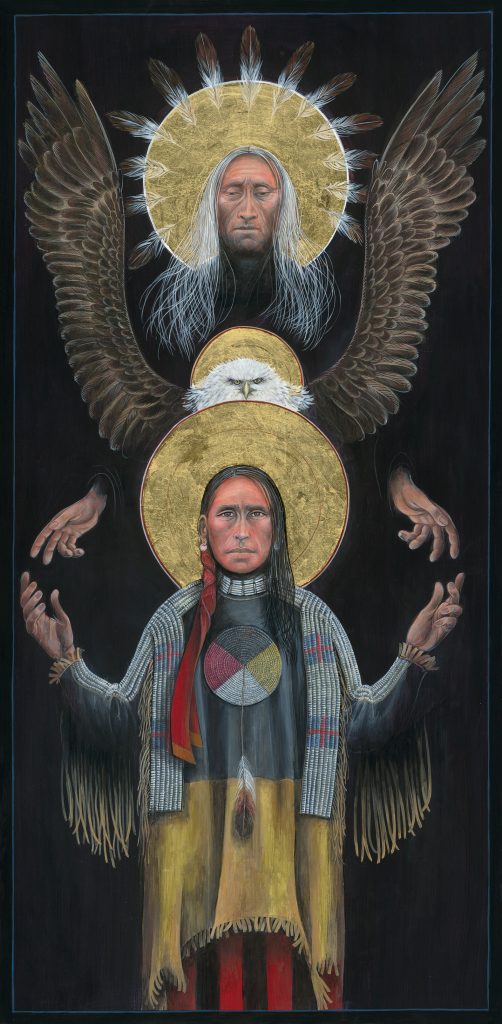

Lakota Trinity

This painting originated when a Jesuit priest, familiar with Giuliani’s work, asked him to paint an image of the Trinity. The Jesuit priest was struggling to convey the church’s understanding of the Trinity to the Lakota people to whom he ministered. Seeing Giuliani’s paintings, the Jesuit priest knew Giuliani’s unique imagery would convey the Trinity’s essence better than any words.

The resulting painting is rich in symbolism, mystery, and power. Drawing from Lakota spirituality and culture, Lakota Trinity portrays a God of strength. Jesus, cloaked in a traditional victory jacket, is accompanied by a keen-eyed eagle representing the Holy Spirit and is watched over by God the Father as he prepares for the final cosmic battle between good and evil. God the Father is depicted as a wise Grandfather spirit, with ethereal hair and battle-ready headdress.

The diffuse light, outstretched hands of the Father and Son, and visual punctuation of halos—in conjunction with their wise yet fierce facial expressions—convey deep unity among Father, Son, and Spirit. Both meditative and charged with potential energy, the painting succinctly and impressively answers the question, “Who is God for us?” God is the God of our ancestors, the God we know, and the God who will overcome the evils of this world.

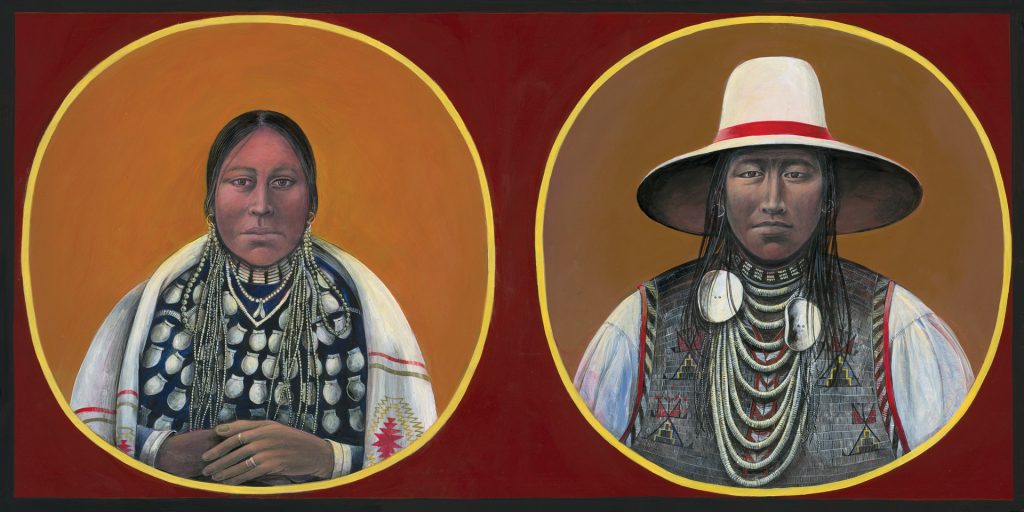

Crow Couple

Perhaps the pinnacle of Giuliani’s art theologically and artistically can be seen in his painting Crow Couple. This work has no overt religious theme, and at first glance a viewer might be tempted to think it peculiar in his oeuvre. In actuality, Crow Couple transcends the notion that a work of art has to be blatantly religious to have deep theological significance. The stillness, solemnity, and stateliness of this couple give the work a monumentality despite its deceptive simplicity. Their penetrating, knowing eyes point to a rich interior life seasoned by life experiences. All sense of time and location has been removed, and we are presented with a different kind of “real presence.”

If an icon painting is, as Father Giuliani says, a “window to the sacred” and an encounter with the divine, Crow Couple is a genuine encounter with both humanity and with God, and a lens by which we see the dignity of the human person.

Catholics believe in a sacramental world—a world where creation is constantly signaling the glory of God. Through Giuliani’s paintings, viewers can see how closely this worldview aligns with the richness of Native American traditions about the presence of the sacred in all things. People, places, and things—even paintings—are able to convey a deep sense of God.

This is a message that is both timely, given Pope Francis’ continued emphasis upon caring for our world, and timeless, in that it predates Columbus and the European presence in the Americas. The gift of Giuliani’s paintings is not only that they show forth the dignity of the human person in a culturally inclusive way, but also that they challenge any narrow reading of God’s presence through history. After all, as Father Giuliani thoughtfully observes of the Native American people, “they were the first spiritual presence in the land.”

Header Image: Marriage of Mary and Joseph, Father John Giuliani

Add comment