Christian music tends to fall into one of two categories: either truly awful or not quite so terrible. But rather than musicians making Christian music, maybe it should be Christians making music. The difference may not look like much, but it is.

Christian music tends to fall into one of two categories: either truly awful or not quite so terrible. But rather than musicians making Christian music, maybe it should be Christians making music. The difference may not look like much, but it is.In the latter category is Sufjan Stevens. In his wildly talented hands, Christian music becomes what it should be. Rather than songs that could replace every “baby” with “Jesus,” Stevens responds to life through the lens of someone who is leaning on God. This shift is honest, artistic, and extraordinary.

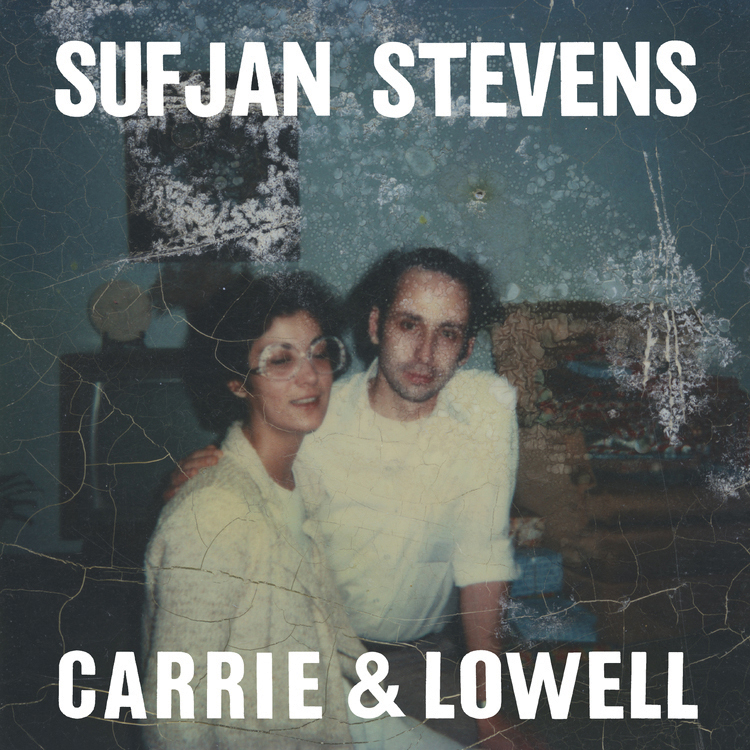

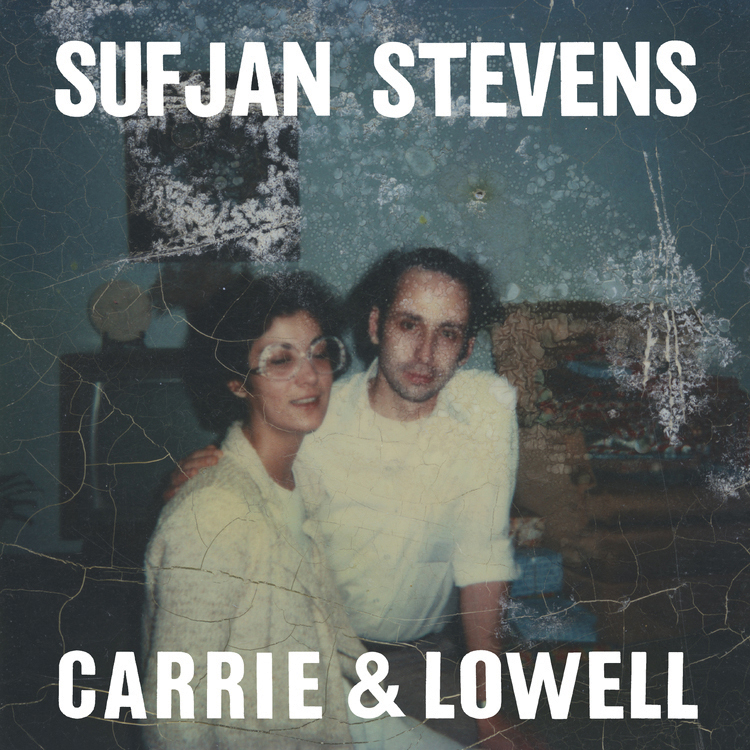

Stevens’ seventh studio album, Carrie and Lowell, is his darkest. This album pursues his mother Carrie, who suffered from bipolar disorder and schizophrenia before dying from stomach cancer in 2012. She left Stevens when he was young, a loss that left him with a melancholy that touches his music. (“When I was 3, maybe 4, she left us at that video store.”)

Lowell is Stevens’ stepfather, the order to the disorder left by his mother. The balance between the two is where God is felt. Stevens recognizes the grace of Lowell in his life in the song “Eugene,” where he sings, “Since I was old enough to speak . . . Some part of me was lost in your sleeve . . . I just want to be near you.”

Carrie and Lowell is Stevens’ soul as a little boy laid bare. The love, the nostalgia, and the pain of the album is almost too much to bear. But its haunting beauty makes it difficult to stop listening. That’s the way it is with grief. We flee from it until we face it and embrace its odd beauty.

In the final song, Stevens sings, “There’s no shade in the shadow of the cross.” The album faces that cross and is resurrected with it. “I should have known better / Nothing can be changed / The past is still the past,” he says. Yet, burying ourselves in unanswerable questions makes us feel closer to what we’ve lost. This is Christian music at its very best.

This review appeared in the June 2015 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 80, No. 6, page 42).

Add comment