We’ve all seen the Hallmark version: the loving, happy, laughing family gathered around the Christmas tree.

Then there’s real life.

Father John Cusick, director of young adult ministry for the Archdiocese of Chicago, remembers the relative who, every year, tried to goad him into a political argument during Christmas dinner. One year he took the bait and the conversation got heated. Later he went home, took a deep breath, and thought: “What a way to ruin a holiday.”

How to ruin the holiday—there are so many ways, from the comedic to the close-to-pathological. We’ve all been there.

There’s the furnace that expires just when the guests arrive.

The ache of missing loved ones who’ve died, or up-and-gone, or the question of whose turn it is to spend the holidays with the in-laws.

Throughout the Advent and Christmas season, Catholics deal with both what’s supposed to be—at least in our imaginations—and what really exists in our families, our jobs, our culture, and our parishes.

“We all have this idea of the holiday as a family gathering, this Norman Rockwell kind of scene,” says Patrick V. Dean, director of Grief Education Services for the Archdiocese of Milwaukee Cemeteries and founder of the Wisconsin Grief Education Center. “It’s a nice visual and it exists, but it’s not everybody’s story. One could argue that it’s almost a minority position—that in all communities and all families, a majority of them have stresses and conflicts.”

Jesus was born into a family that had its own Christmas drama of sorts—an unmarried pregnant woman, a long hard trip, and a no vacancy sign at the local motel. He was born into a broken world. For that reason some suggest that Christmas is exactly the time to live out in our own imperfect families the kind of reconciliation that God offers to us. Our efforts to make the best of our messy family celebrations could be one way of bringing Christ’s spirit into the world.

Playing referee

Phil Fox Rose’s family is all over the place—geographically, spiritually, and politically. His parents left the Mormon church; his father became atheist and his mother is “kind of vague” about religion. Of their six children, one is Mormon, one an evangelical Protestant, one attends a liberal Protestant church, two are unaffiliated, and Rose, a 48-year-old writer from New York, became Catholic.

“We’re very scattered,” Rose says—and most of the time, the East and West Coast sides of the family do not get together.

When they do, Rose has learned not to bring up issues such as national elections or universal health care—or if it does come up, to “gently suggest that the other side isn’t evil.” He tries to be a healing force—and to suggest holiday gatherings at least for the siblings who live closer together.

That doesn’t always happen. But like a lot of people who have close connections with their “families of choice”—friends, close co-workers, and neighbors—Rose has made his own traditions. He often celebrates Christmas with a blend of Presbyterians, Buddhists, and Jews, who have become a second family to him.

Rose, who is divorced, says he understands the stress that single people with scattered families can feel during Christmas. He has friends “who are really kind of irritable at the holidays, almost angry at the fact that the focus is on families coming together. It’s kind of rubbing it in their face that they don’t have one.”

Forget Currier and Ives

Part of the strategy for coping may be a dose of realism.

“The greater the difference between what you expect is going to happen and what happens, the greater your stress will be,” says Mary Jo Pedersen, a teacher and author who worked for the Family Life Office in the Archdiocese of Omaha until retiring in 2008. “We have so commercialized Christmas and romanticized it and perfected it—your house looks a certain way and your tree, your clothes, your parties, your gifts—the expectation of what it [should be] is unrealistic.”

It may be more realistic, she says, to anticipate stress and tension and not be surprised when it pops up. Most people celebrate Christmas with extended family, which makes things even more complicated.

“We have to look at the realities of extended families. Almost half of marriages end in divorce every year,” Pedersen says. “Eighty percent of those who divorce remarry. So many families are accepting a new member.”

It’s hard enough to hold tight to the spiritual meaning of the season that becomes too jammed with shopping, cooking, parties, travel, and expectations. Mix in lost jobs, overspending, crying babies, aging parents, moody teenagers, people who drink too much, gay and lesbian relatives and their partners, plus relatives who think homosexuality is a sin—and then put everyone all under one roof.

For those who are single, “you’re going to run into the question of ‘Why aren’t you married?’” says Cusick. “That’s the fear of a lot of younger single people when they go home. The other one would be ‘alternative lifestyles.’ How welcome is the young adult in the family who’s not doing it the way it’s ‘supposed’ to be done.”

An “alternative lifestyle” can mean a lot of things, Cusick explains—the son or daughter who’s dropped out of church or switched religions, who’s living with a partner with no wedding in sight, who’s decided to travel or make music instead of getting a “real job.”

“Are people welcomed in Christ and not turned away at the inn because there’s no room?” Cusick asks.

Pedersen speaks of the family as a “school of love,” using the words of Pope John Paul II in his 1981 message Familiaris Consortio. “That doesn’t mean to have affection for them,” she “It means loving them as God loves. For us believers the family is the place where we can provide for each other and receive unconditional love.”

‘Tis a gift to be flexible

For some, a key survival strategy for the Christmas holidays is flexibility and a spiritual focus.

That might mean being flexible as a guest in someone else's home, but it can also mean showing flexibility as a host. Maybe you’ve always served exactly the same food in exactly the same dishes—year after year, at your own home. And maybe this is the year when the new daughter-in-law wants to bring the meatballs her family always has on Christmas. Or maybe she wants you to come to her home for meatballs instead of turkey.

Roxane Salonen, a freelance writer and mother of five from Fargo, North Dakota, established the pattern from the beginning of her marriage of alternating the Christmas holidays between her family and her husband’s.

“Trying to make it work for both would be impossible for us,” she says. “We bring seven people along. It’s kind of crazy when we come. It works for everyone not to expect that every holiday will be covered.”

They have also decided that the adults would not give each other presents, and that the children would exchange small, mostly handmade gifts. “We used to try to keep up with the Joneses,” Salonen says. “It wasn’t working.”

And they’ve learned to be flexible about observing Christmas at church. Salonen and her husband are Catholic, but his parents attend a Protestant church. Sometimes Salonen will go by herself to Midnight Mass on Christmas Eve—“I remember some really peaceful Midnight Masses,” she says—or sometimes she and her husband will take the older kids along as a special treat while the grandparents watch the little ones.

Sometimes the changes in tradition come because the family itself has changed. Families where there’s been a divorce or separation may suddenly, if there’s been a remarriage, have four sets of grandparents to juggle. Or sometimes a former spouse is just gone—not involved with the family at all.

Mary Armento, who helps run a divorce ministry program at Prince of Peace Catholic Church in Flowery Branch, Georgia, speaks of the difficulty for newly divorced or separated people of getting through the “Big Three”—Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s Eve.

“Divorce is a process, it is not an event,” Armento says. “It takes a long time to get through it. It takes a lot of hard work to get to the other side of it.”

Leading into the holidays, she stresses forgiveness and reconciliation.

“What Christ calls us to do is to forgive others—that’s where true healing begins,” Armento says. “When you’re divorced, especially if you have children, you’re always going to be part of each other’s lives. You have to find a place not necessarily to be best friends, but where you can co-exist without all that anger and bitterness.”

That kind of reconciliation can be part of Advent preparation, Pedersen says. “Christ reconciled the world to God. Our job is to make Christmas a time of reconciliation and peace.”

Blue Christmas

For those who are grieving, the stress of the holidays can mean “you have a recipe for some real painful times,” says Dean, who works with the grief program in Wisconsin. Some will spend too much money. Some try to do too much while others pull back.

“What people often miss is that it’s OK, in fact it’s healthy, to seek a balance,” Dean says. “What people try to do is to deny their sadness, to deny their grief, to try to ‘be strong,’ saying, ‘I don’t want to cry in front of my children or grandchildren.’ ”

“It’s OK to be sad,” he says. “That’s what I say to people over and over again during the holiday season. If you need permission, consider it granted.”

It’s also OK to show emotion, to have the tears. “You can say, ‘Grandma’s sad right now. She’s missing Grandpa. He would have loved to be here today.’”

Some families, having experienced a loss, will build some time into their holiday celebration to share memories, look at photos, and tell stories of the person who has died.

Parishes also can play a role in helping Catholics keep a balance during the Christmas season by offering resources for serving others and observing Advent, and by acknowledging openly that not everyone finds Christmas a rollicking time of family joy.

For the past four years now, the St. Thomas More Newman Center in Columbus, on the campus of Ohio State University, has held a “Blue Christmas” Mass at 8 p.m. on Christmas Eve.

Father Larry Rice, the Newman Center’s director, had the sense that Christmas is a struggle for lots of folks—for lots of reasons.

“We really want to reach out to people who are feeling alienated from the church or disconnected from society, and try to bring them some healing,” Rice says. “I wanted to do something that was really going to be about welcoming people who have a hard time with the holidays.”

The idea is to celebrate the Incarnation, but in a quieter, more subdued way.

“You really don’t have to do ‘Joy to the World’ at every Mass,” Rice says. “We do the more quiet, reflective Christmas songs. We start the liturgy by simply welcoming people, acknowledging that not everybody feels great about Christmas. We invite people to bring with them whatever they’re going through and whatever they’re struggling with, and to know that all of that is welcome.”

Rice preaches a homily about the core meaning of Christmas. “Christ [became] one of us here on the ground and [lived] through all the struggles we live with,” he says. “All of our human experience is redeemed, even the difficult parts. Jesus is there to acknowledge and heal whatever is within us that's broken, and to be with us in all our struggles.”

As they leave, each worshiper receives a poinsettia, donated by a local nursery. That means each person will receive at least one gift for Christmas.

From the altar, Rice can look across the crowd and see people crying.

The first year, after the Mass had ended, a woman came up to Rice with tears streaming down her face. “It was the first time she didn’t feel out of place at Christmas in 25 years,” he says. “I thought, ‘What has she been carrying around for 25 years that was so horrible?’ I never found out.”

This article appeared in the December 2009 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 74, No. 12, page 12).

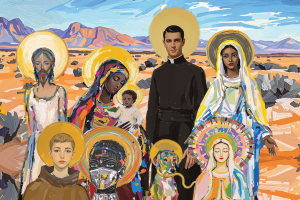

Image: Wesley Tingey on Unsplash

Add comment